Much has been written about the relationship between postmodern thought and the problem of  uncertainty in the church. We might infer from this that the church didn’t have this kind of problem in the good-old-days of modernity. While revisiting the J. I. Packer’s God Has Spoken (released in 1965), I was reminded that the problem of uncertainty is not unique to today’s church:

uncertainty in the church. We might infer from this that the church didn’t have this kind of problem in the good-old-days of modernity. While revisiting the J. I. Packer’s God Has Spoken (released in 1965), I was reminded that the problem of uncertainty is not unique to today’s church:

“ . . . at no time, perhaps, since the Reformation have Protestant Christians as a body been so unsure, tentative and confused as to what they should believe and do. Certainty about the great issues of the Christian faith and conduct is lacking all along the line. The outside observer sees us as staggering on from gimmick to gimmick and stunt to stunt like so many drunks in a fog, not knowing at all where we are or which way we should be going. Preaching is hazy; heads are muddled; hearts fret; doubts drain our strength; uncertainty paralyses action. We know the Victorian shibboleth that to travel hopefully is better than to arrive, and it leaves us cold. Ecclesiastics of a certain type tell us that the wish to be certain is mere weakness of the flesh, a sign of spiritual immaturity, but we do not find ourselves able to believe them. We know in our bones that we were made for certainty, and we cannot be happy without it. Yet, unlike the first Christians who in three centuries won the Roman world, and those later Christians who pioneered the Reformation, and the Puritan awakening, and the Evangelical revival, and the great missionary movement of the last century, we lack certainty. Why is this? We blame the external pressures of modern secularism, but this is like Eve blaming the serpent. The real trouble is not in our circumstances, but in ourselves.” (God Has Spoken, (Baker, 1979 [reprint ed.]), 20.)

Packer goes on to explore the question of why uncertainty plagues the church, and what happens as the result:

“ . . . it is not as if the Bible were no longer read and studied in our churches. It is read and studied a great deal; but the trouble is that we no longer know what to make of it. Mesmerized by the problems of rationalist criticism, we can no longer hear the Bible as the Word of God. Liberal theology, in its pride, has long insisted that we are wiser than our fathers about the Bible, and must not read it as they did . . . . This insistence has a threefold effect. It produces a new papalism --- the infallibility of the scholars, from who we learn what the ‘assured results’ are. It raises a doubt about every single biblical passage, as to whether it truly embodies revelation or not. And it destroys the reverent, receptive, self-distrusting attitude of approach to the Bible, without which it cannot be known to be ‘God’s Word written.’ . . . The result? The spiritual famine of which Amos spoke. God judges our pride by leaving us to the barrenness, hunger, and discontent which flow from our self-induced inability to hear his Word.” (Ibid., 21)

These words sound a timeless note. Yesterday, the church was uncertain because the culture insisted that authentic knowledge was grounded in the rational assessment of empirical data. Today, the church is uncertain because the culture insists it knows that authentic knowledge is not even possible. Words --- we are told --- are especially suspect; they are merely symbols referring to other words; they are but tools for those who would make a play for power over others. And so a great many words have been written to assure us that words are not reliable and that uncertainty is certain.

These words sound a timeless note. Yesterday, the church was uncertain because the culture insisted that authentic knowledge was grounded in the rational assessment of empirical data. Today, the church is uncertain because the culture insists it knows that authentic knowledge is not even possible. Words --- we are told --- are especially suspect; they are merely symbols referring to other words; they are but tools for those who would make a play for power over others. And so a great many words have been written to assure us that words are not reliable and that uncertainty is certain.

Packer’s insight is a helpful reminder: the reason why the church struggles with what to believe and how it should act is not on account of prevailing cultural thought. Rather, the reason lies within the church. The church boldly affirms its confidence in Scripture, but quietly entertains the latest assurances promised by culture and the academy. Equivocation of this sort, and not the culture, is at the root of uncertainty in the church. The church’s equivocation on the clarity and trustworthiness of Scripture may be attributed to culture as much as Eve’s disobedience can be blamed on the serpent.

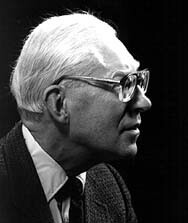

Eric Lehner is the Professor of Theology at Virginia Beach Theological Seminary.